This information has been compiled using publicly available information on established best practices. ASHP and the University of Utah have provided this fact sheet for informational purposes only and are not assuming any liability for the accuracy or completeness of the information provided.

Updated 11/25/2024. Updates highlighted for reference.

Recent Updates:

- Safe Use of Imported Products

- Additional links in External Resources

Please email PracticeAdvancement@ashp.org with comments or questions.

Introduction

This fact sheet provides potential actions for organizations to consider in managing fluid shortages. Healthcare practitioners should use their professional judgment in deciding how to use the information in this document, considering the needs and resources of their individual organizations.

Why is conservation necessary?

There is a national shortage of large-volume parenteral solutions, including but not limited to: sodium chloride injections, Lactated Ringers injection, Sterile Water for Injection, and Dextrose injections. The shortages are due to the effects of Hurricane Helene in North Carolina.

Definitions

Small-volume parenteral solutions (SVPs) — a solution volume of 100 mL (as defined by USP) or less that is intended for intermittent intravenous administration (usually defined as an infusion time not lasting longer than 6-8 hours).1

Large-volume parenteral solutions (LVPs) – a solution volume of greater than 100 mL (as defined by USP)

Intravenous (IV) push — The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) defines IV push as “direct, manual administration of a medication using a syringe, usually under pressure, connected to an IV access device.”2 Best practice recommends that whenever possible the actual rate of IV push administration specific to a given drug be noted and that terms such as IV push (unspecified), IV bolus (unspecified), slow or fast/rapid IV push should be avoided.

Ready-to-administer — A dosage form or concentration that can be administered to the patient without further manipulation

General Recommendations

- Implement an organization-specific action plan to conserve IV fluids where possible. Organizations must be flexible as the status of specific products may vary. Establish policies to allow for interchanges between clinically equivalent products when possible.

- Ensure an interdisciplinary team is making rationing decisions using an ethical framework.3

- Establish a schedule to regularly assess restrictions and adjust based on current and anticipated supply.

- Communicate changes in shortage status and action plan adjustments to stakeholders as soon as possible.

- Identify vulnerable patients and populations with specific needs, such as pediatric and neonatal patients, and consider specific policies and practices that reserve or prioritize fluid products for their needs.

Conservation - Large Volume Products

- Evaluate the clinical need to continue intravenous fluid replacement at every shift change and bag change.

- Assess the need to initiate “keep vein open” (KVO) orders and the need to continue those orders at every shift change.

- Review the organization’s standard KVO rates and consider reducing to the lowest reasonable rate.4

- Consider catheter locks with flushes for eligible patients.

- Use oral electrolyte and hydration whenever possible.5

- Discontinue infusions as soon as appropriate.

- Avoid discontinuing and restarting intravenous fluids during transitions of care (such as between the emergency department and other nursing units) unless clinically necessary.

- Consider policies that allow completion of a currently hanging infusion bag before switching to a different infusion product unless clinically contraindicated.

- For example, if an order is changed from 0.9% sodium chloride to dextrose 5% with 0.45% sodium chloride, consider allowing completion of the bag of 0.9 % sodium chloride before switching to prevent waste and prolong the total infusion time of available fluids.

- Evaluate total fluid requirements for surgeries and transition to oral fluids within 24 hours after surgery.6

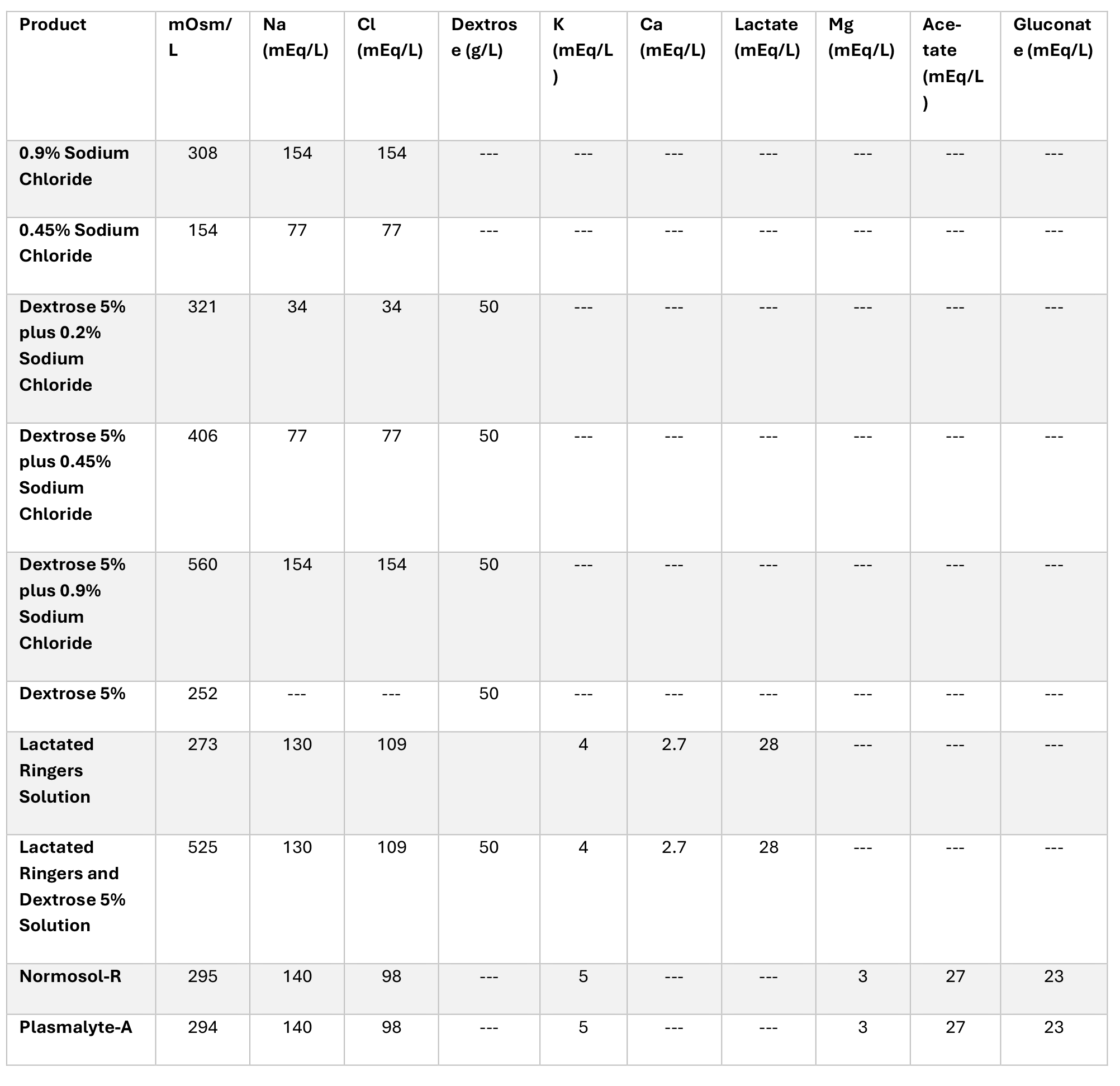

- Develop policies for substitution of intravenous solutions based on product availability in the organization. Example: an organization might allow substitution of Lactated Ringers for 0.9% sodium chloride or vice-versa depending on what is in stock. Table 1 provides a comparison of common intravenous fluid components. The Emergency Care Research Institute (ECRI) has also published a Supply Chain Report on equivalent and alternative IV solution and irrigation products.

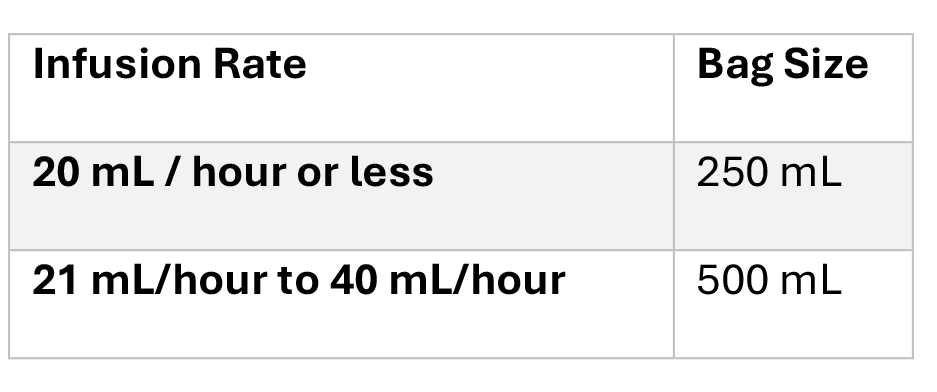

- Use smaller volume bags for low infusion rates (see Table 2).

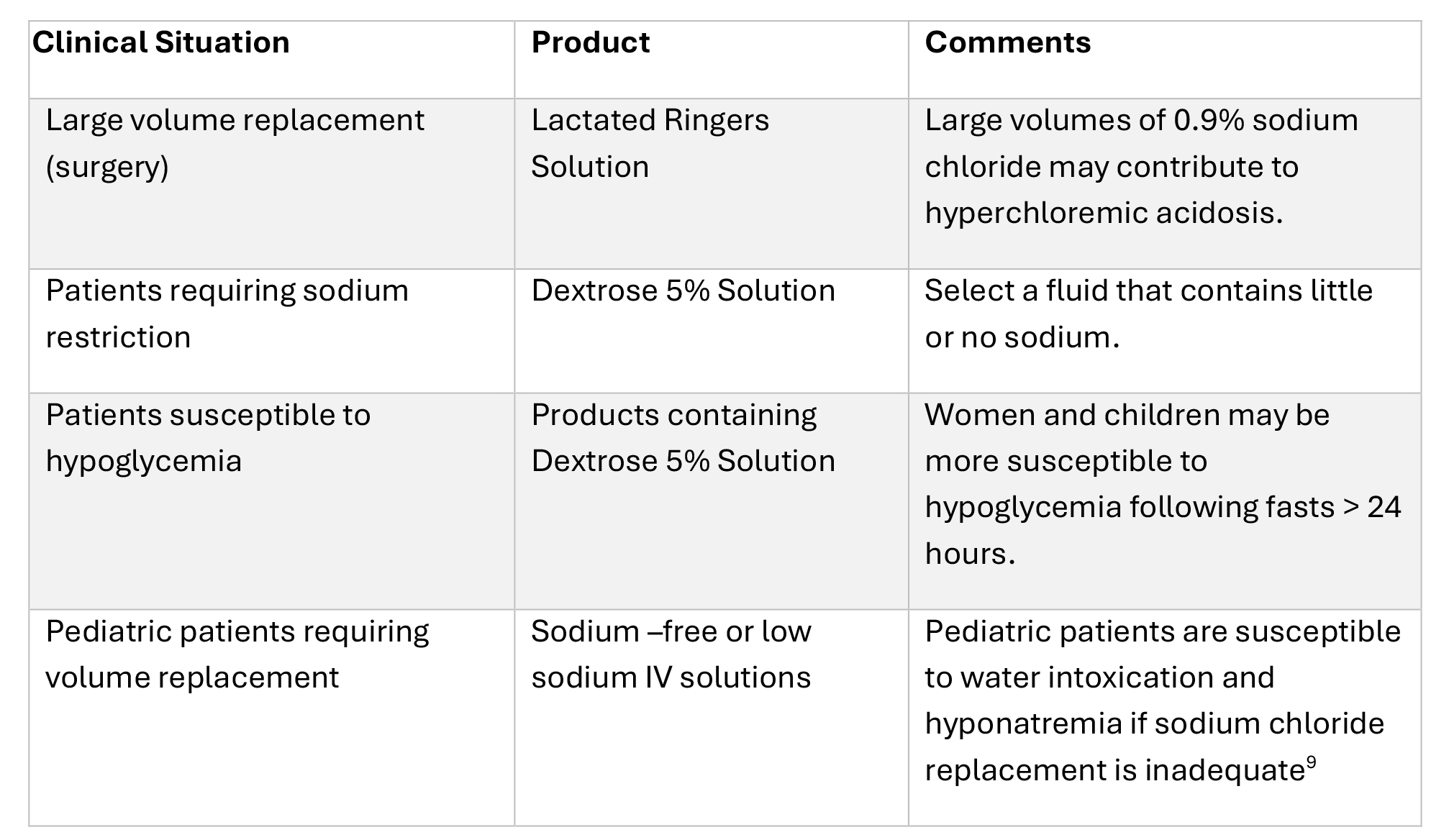

- Consider reserving some products for specific clinical situations as outlined in Table 3.

- Avoid opening and “pre-spiking” bags in anticipation of use for surgery.

- Use other large volume electrolyte replacement solutions where appropriate.

- Consider extending hang times for intravenous solutions (if spiked immediately prior to administration). The 2024 Infusion Nurses Society Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice note that there is insufficient evidence to recommend a specific frequency for routine replacement of non-lipid IV fluids.7 Evidence shows no difference in central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) rates at 96 hours for fluids administered via central venous catheters.8 In making such a decision, hospital leadership; medical, nursing and pharmacy staff; infection control; risk management and other stakeholders should weigh the risk of infection against the need to conserve intravenous solutions. See FAQs section for more information.

- Review use of sterile water for rinsing equipment or utensils used during nonsterile compounding. USP Chapter <795> Pharmaceutical Compounding—Nonsterile Preparations specifies that purified water, distilled water, or reverse osmosis water should be used to rinse equipment or utensils.9

- Review use of sterile water for reconstituting conventionally manufactured oral solutions. Follow product labeling instructions for water requirements. Note that reconstituting conventionally manufactured nonsterile products according to product labeling is not considered compounding according to USP Chapter <795>. However, compounding nonsterile preparations does require the use of USP-compliant purified water or better-quality water.9

Conservation - Small Volume Products

- Review the use of fluids as supplies. Many areas use SVP fluids to start intravenous lines, administer blood, or flush lines. During these shortages, consider using single-use flush syringes when possible, although these products can also be affected by shortages.

- Switch products to IV push when the patient’s clinical status drug properties (e.g., pH, osmolarity) allow. Follow ISMP Safe Practice Guidelines for Adult IV Push Medications.2

- Adhere to the CDC use guidelines for single-use vials.10

- Change IV medications and electrolytes to a clinically appropriate oral product whenever possible.

- Work with the organization’s P&T committee, or equivalent, to review current IV to oral (PO) policies.

- Policies may need to be expanded to include other drug classes.

- If oral route is not feasible or indicated, some medications can be administered via intramuscular or subcutaneous injection.

- Adhere to recommended maximum volumes for a single injection; doses may need to be divided into more than one syringe.

- Consider alternative intravenous solutions when therapeutic interchange is not clinically important (e.g., maintaining line patency, for blood administration, etc.).

- Review the stock of small volume bags and vials to determine stock on hand that is compatible with proprietary bag-and-vial systems.

- Do not make practice change plans that will require additional fluids or specific products (e.g., requiring additional mix-on-demand supplies).

Conservation – Irrigation Solutions

- If considering irrigation substitution, review available equivalent and alternative products in the ECRI Supply Chain Report.

- Per American College of Emergency Physicians recommendations, consider using tap water instead of IV or sterile irrigation solutions for wound cleansing when clinically appropriate.11

- Identify sterile fluids that are being used as cleaning solutions. Contact equipment manufacturers to determine if other fluids such as distilled water can be used during the shortage.

- Avoid using sterile water for irrigation for routine reconstitution of oral products, or for other uses inside the pharmacy such as preparing solutions for leeches.

- Consider if any pre-mixed commercial irrigation solutions can extend irrigation volumes.

- Use of CRRT solutions or inhalation solutions as irrigation solutions may create additional shortages of these products.

- Evaluate whether conserved IV solutions can be used as irrigation solutions.

Operational Strategies – Large Volume Shortages

- Evaluate supplies on a health system-wide basis to redeploy solutions to areas of greatest need.

- Minimize unit stock of large volume bags to the extent possible or stock only in critical care, procedure, and emergency care areas where fluids are an essential component of supplies.

- Ensure smaller volume bags are stocked in supply areas.

- If conservation of SVP bags is necessary, stock only in areas where medications must be prepared so that supplies can be consolidated.

- Work closely with the supply chain team to obtain accurate system-wide estimates of stock on hand, particularly in health-systems where pharmacy does not supply all fluids.

- Evaluate whether fluids are utilized to help administer secondary infusions and if those fluids are accounted for in overall counts.

- Consider using smaller volume bags or vials of saline and sterile water for reconstituting drugs in the pharmacy instead of using liter bags.

- For situations where small volumes are required but small volume packages are not available (e.g., lactated ringers solution), aliquots of fluids drawn into syringes in the pharmacy may allow a bag of fluid to be used on multiple patients if syringe pumps can be used.

- For example: 50 mL syringes drawn out of a liter bag of lactated ringers solution may allow a single liter bag to be used for multiple patients during a minor or short procedure.

- Follow USP Chapter <797> and state rules and regulations for determining applicable beyond-use dates.12

- Medicare will not reimburse for oral hydration in the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS). This applies to patients in ambulatory care settings and patients in the ED who are not admitted to the hospital. Medicaid patients are reimbursed in accordance with state-based policy.

- Avoid buying products from sources outside the traditional supply chain. Report suspected illegal activity by nontraditional distributors to your state board, state attorney general, or FDA’s Office of Criminal Investigation. Report price gouging to the Department of Justice.

Operational Strategies – Small Volume Shortages

- Transition to commercially manufactured premix medications when available.

- If switching to IV push, ensure sufficient supplies of diluent vials, syringes, and needles are available to accommodate these doses.

- Leverage admixtures available from 503B outsourcers when available.

- Also communicate with 503B outsourcers to understand how their supply may be affected by shortages.

- Consider changes in the electronic health record (EHR) to allow the use of either dextrose or saline for admixture of drugs compatible with both solutions. This will help create better flexibility based upon which products are available at the time.

- Use EHR alerts or forced functions when a drug is compatible in only one diluent.

- Implement or encourage the use of barcode scanning of admixture ingredients to ensure the correct solution is used and documented.

- Consider preparing and dispensing medications that may be administered IV push in ready-to-administer concentrations packaged in syringes.

- External references are available with information on concentrations and administration rates. See the External Resources section for additional information.

- If your organization can utilize syringe infusion pumps, consider preparing and dispensing non-IV push medications in ready-to-administer syringes to be infused via syringe pump.

- If empty bags are available, and all other options have been exhausted, consider compounding SVPs of 5% Dextrose or 0.9% Sodium Chloride. This may not be possible if the fluid shortage includes both SVPs and LVPs. See FAQs section for more information.

- The preferred method for these preparations is to use 1 L bags of commercially available 5% Dextrose or 0.9% Sodium Chloride to repackage into smaller bag sizes (50, 100, or 250 mL).

- Peristaltic pumps may be used for compounding and will help ensure accuracy and minimize employee fatigue and over-use injuries.

- Follow USP Chapter <797> and state rules and regulations for determining applicable beyond-use dates.12

- If compounded or repackaged bags have been frozen to extend dating, thoroughly inspect the bag before dispensing to ensure the bag did not crack or split during frozen storage.

- Only compound in an empty container that adequately reflects the final volume: for example, 100 mL of solution in a 100 mL empty container.

- If necessary to compound in a bag with larger capacity than the final volume of solution, the pharmacy label should be affixed so that it covers the empty capacity printed on the bag. For example, if compounding 50 mL total volume in a 150 mL container the pharmacy label should cover the 150 mL print on the bag.

- Ensure that the temperature for refrigerators and freezers are continuously monitored.

- Double check that they are plugged into emergency power outlets.

Operational Strategies – Irrigation Shortages

- Work to identify which surgical procedures utilize the largest volumes of irrigation. Consider if any of these surgeries could be rescheduled.

- Identify all areas of the organization that use irrigation fluids. Surgery volumes may be sporadic, so consider using past purchases to establish a usual rate of use.

- Consider manual counts in OR areas to ensure accurate on-hand quantities.

- Set internal allocations to prevent one area from using more than their share. Consider identifying a small number of people who may order and pick up these fluids from the central supply area.

- Evaluate surgery schedules and the usual volumes of irrigations needed with the quantities on hand to determine if all surgeries can proceed.

Infusion Pumps / Informatics Strategies

- Allocate appropriate clinical informatics resources to manage critical shortages.

- Review order sets and preference lists for fluid orders that have been selected by default, including KVO orders, and update when possible.

- Individual prescribers may have manually overridden order-set defaults and to a personal preference list. Develop a process to identify these personal selections and update them when possible. Overriding personal versions may require manually adjusting each saved version.

- Consider alerts to notify clinicians when fluids are ordered for patients tolerating oral hydration.

- Ensure existing pump libraries are up to date to ensure safe and consistent practices.

- It may be necessary to change or add to drug libraries. If so, use clinical, safety/quality, and informatics teams to ensure that any additions or changes have been vetted through appropriate channels.

- Drug records, order-sets, and treatment protocols will need to be reviewed for changes based on available products.

- These may include solutions used for medication dilution or solutions available for line patency.

- Reflect use of smaller volumes in infusion pump libraries, electronic order sets, and standard fluid labels as needed.

- Take the opportunity to review, revise, or develop good infusion pump practices and protocols.

- Consider where and when other types of ambulatory infusion pumps can be used.

- Try to maintain standardization whenever possible, especially if the same pumps are used for both adult and pediatric patients.

Communication Strategies

- Adequately communicate any changes to current practice using established communication channels within your hospital or health system, such as local intranet, EHR alerts, emails, daily huddles, flyers, labeling, etc.

- Be sure that the clinical informatics team is aware of the need to make priority changes in drug records, charge description masters, and infusion pump libraries and recognize that they will not have the normal lead time that this process generally requires.

- Consider having a physician and nursing champion in addition to the pharmacy lead who can assist with routine communication, practice changes, and stock updates.

Safety Considerations

- Compounding sodium chloride solutions from sterile water for injection and concentrated sodium chloride injection is labor-intensive and may worsen the existing shortage of concentrated sodium chloride injection. For urgent short-term sodium and fluid replacement therapy, consider adding concentrated sodium chloride to dextrose or other commercially available large volume parenterals.

- Avoid use of sodium chloride irrigation solution administered intravenously. Limits on particulate matter differ between these two products.

- Make sure all healthcare professionals administering medications have access to IV push policies and guidelines and have been trained and assessed for competency in administering medications via the IV push route. Use available best practices and concepts for IV push administration.2

- Consider an IV push administration competency assessment tool if one is not already in place.

- Do not allow the use of “stock” bags that could potentially be used for multiple patients.

- If transitioning medications to syringes for syringe infusion pump administration, make sure staff are adequately trained to use the technology.

Safe Use of Imported Products

Baxter is working with the FDA to identify and import products to mitigate the impact of fluid shortages. Baxter has established a website with details about imported products and resources to help clinicians understand differences in appearance and composition for the imported fluids.

ISMP has published considerations for safe use of imported products, including an Imported Fluid Product Checklist.

ASHP has published a Fluid Shortage: Importation Risk Mitigation Strategies document with strategies to reduce the potential risks with use of imported products.

ISMP Medication Error Reporting

ASHP encourages the reporting of any medication errors related to drug shortages to the Medication Error Reporting page on the ISMP website.

External Resources

- Hurricane Helene Updates: Baxter Healthcare Corporation

- Hurricane Helen Clinical Resources: Baxter Healthcare Corporation

- Hurricane Helene: Baxter’s manufacturing recovery in North Carolina: Food and Drug Administration, 2024

- Temporary Policies for Compounding Certain Parenteral Drug Products: FDA, 2024

- Disruptions in Availability of Peritoneal Dialysis and Intravenous Solutions from Baxter International Facility in North Carolina: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024

- Intravenous Fluid Shortage Strategies: Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response, Technical Resources, Assistance Center, and Information Exchange, 2024

- Operational Considerations for Sterile Compounding during Public Health Emergencies and Natural Disasters: United States Pharmacopeia (USP)

- Complimentary access to select USP monographs for medications affected by the fluid shortage: USP

- Weathering the Storm—Safety Considerations during Fluid Shortages: ISMP, 2024

- Fluid shortage update—Safeguard imported products: ISMP, 2024

- Hospital-Based Oral Rehydration Strategy: NEJM, 2018

- Adult and pediatric IV push medication reference: Vizient, Inc. 2023

- Intravenous fluid conservation strategies: Vizient, Inc. 2024

- ISMP Safe Practice Guidelines for Adult IV Push Medications: ISMP, 2015

- Intravenous Push Administration of Antibiotics: Hosp. Pharm, 2018

Resources and Recommendations from Other Professional Organizations:

- Clinical Alert: Conservation of IV Fluids Urged with NC Manufacturing Factory Closed: American College of Emergency Physicians

- Updates on IV Fluid Supplies: American Hospital Association

- 2024 Parenteral Nutrition Product Shortage Recommendations: Intravenous Dextrose: American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

- 2024 Parenteral Nutrition Product Shortage Recommendations: Sterile Water for Injection: American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

- Hurricane Helene Baxter Shortages: American Society of Anesthesiologists

- Interim Strategies for Conservation of Peritoneal Dialysis (PD) Solution: American Society of Nephrology

- Interim Guidance on PD Solution Conservation During Supply Shortage: American Society of Pediatric Nephrology

- Update on Intravenous Fluid Shortages: Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses.

- Supply Chain Report (comparison tables for equivalent and alternative IV and irrigation solutions): Emergency Care Research Institute

- Alliance Resources: End Drug Shortages Alliance

- INS Guidance to Address IV Solution Shortages as a Result of Hurricane Helene: Infusion Nurses Society

- Guidance Document for Managing Product Shortages during Disruptions in Manufacturing: National Home Infusion Association

- IV Solutions Supply Chain Disruptions: Society of Critical Care Medicine

- SGO Clinical Practice Advisory: Intravenous Solutions Shortage Guidelines: Society of Gynecologic Oncology

Acknowledgements

ASHP thanks Erin Fox, PharmD, MHA, BCPS, FASHP, and the ASHP Section of Inpatient Care Practitioners Advisory Group on Compounding Practice for their contributions to this resource.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can hospital pharmacies compound IV fluids that are in short supply?

FDA guidance allows hospital pharmacies (categorized as 503A pharmacies) to compound versions of drugs that are essentially copies of commercially manufactured drugs if they are posted on the FDA Drug Shortages List. While this may be possible in some limited quantities, the amount that a hospital pharmacy can compound is not likely to be nearly enough to meet the normal daily use of these fluids in a hospital setting. The products necessary to compound fluids, such as sterile water for injection, concentrated sodium chloride, and empty sterile containers, are also in short supply or likely to be available only in limited quantities. Pharmacies choosing to compound using concentrated sodium chloride solution should take extra precautions and implement in-process double checks due to the risk of serious harm if sodium chloride solutions are compounded incorrectly.

Will Baxter extend expiration dates for products in short supply?

Baxter has announced extended expiration dates for many products affected by the plant closure. Check

the Baxter Hurricane Helene Updates page and Hurricane Helene Clinical Resources page for

information related to expiration date extensions.

Will the FDA authorize importation of fluids from other countries?

FDA and HHS officials have stated that they are exploring all options to help relieve the fluid shortages, including importation. Some products have already been authorized for importation. Check the FDA’s Hurricane Helene page for the latest information.

What is the basis for suggesting longer hang times for IV fluids?

While researching hang times for intravenous fluids, we were unable to find an established standard for recommended hang times. The citation demonstrates no increase in risk of catheter-related bloodstream infections (CLABSI) at 96 hours for central venous catheters.8 This provides some evidence that 96 hours is an acceptable hang time and reasonable extrapolation can be made to peripheral venous access contamination. The Infusions Nurses Society and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that administration sets in continuous use, but not used for blood, blood products, or lipids, be changed "at least every 7 days (unless otherwise stated in manufacturers’ directions for use) or when clinically indicated … , whichever occurs sooner”.7 Organizations should consider the criticality of fluid supply, and clinical risk factors and other variables when making decisions on hang times up to or beyond 96 hours.13,14 Connections and disconnections should be minimized when possible, and aseptic technique should be used at all times when connecting fluids to administration sets and when spiking bags. There are many different types of vascular access devices and organizations should consider risk factors associated with each when establishing fluid hang times.

Will the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) provide considerations for extending the beyond-use dates of compounded preparations to reduce waste like they did during the COVID-19 public health emergency?

USP recently published a resource titled Operational Considerations for Sterile Compounding by Pharmacy Compounders Not Registered as Outsourcing Facilities during Public Health Emergencies and Natural Disasters to help compounders address fluid shortages.

Can the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) help provide sterile fluid supplies to healthcare practitioners?

Any sterile fluid inventory maintained in the SNS is insufficient to meet even a fraction of daily national needs; we do not expect the SNS will realistically provide relief for ongoing shortages.

Table 1. Comparison of Selected Intravenous Fluid15-20

Table 2. Recommended Container Volumes Based on Infusion Rates

Table 3. Considerations for Reserving Products for Selected Clinical Situations21-23

References

- General Chapter: USP. Packaging and Storing Requirements <659>. In: USP-NF. Rockville, MD: USP; May 1, 2017.

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. ISMP Safe Practice Guidelines for Adult IV Push Medications. 2015.

- Hick JL, Hanfling D, Courtney B, Lurie N. Rationing Salt Water – Disaster Planning and Daily Care Delivery. 2014 Apr; 370:1573-1576.

- Paquet F, Marchionni C. What is your KVO? Historical perspectives, review of evidence, and a survey about an often overlooked nursing practice. J Infus Nurs. 2016 Jan-Feb;39(1):32-7.

- Patino AM, Marsh RH, Nilles EJ, Baugh CW, Rouhani SA, Kayden S. Facing the Shortage of IV Fluids – A Hospital-Based Oral Rehydration Strategy. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1475-1477.

- Miller TE, Myles PS. Perioperative Fluid Therapy for Major Surgery. Anesthesiology. 2019 May; 130:825-832.

- Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice, 9th Edition. J Infus Nurs. 2024 Jan-Feb;47(1S Suppl 1):S1-S285.

- Mianecki TB, Peterson EL. The Relationship Between Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections and Extended Intravenous Solution Hang Times. J Infus Nurs. 2021 May-Jun 01;44(3):157-161.

- General Chapter: USP. Pharmacuetical Compounding—Nonsterile Preparations <795>. In: USP-NF. Rockville, MD: USP; May, 2024.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injection Safety, FAQs about Single-dose/Single-use vials, 2019.

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Timely Council Resolution Encourages Using Tap Water for Wound Irrigation. Oct 7 2024. Available at: https://www.acep.org/news/acepnewsroom-articles/timely-council-resolution-encourages-using-tap-water-for-wound-irrigation. Accessed 10/30/2024.

- General Chapter: USP. Pharmaceutical Compounding—Sterile Preparations <797>. In: USP—NF. Rockville, MD: USP; May, 2024.

- Rickard CM, Vannapraseuth B, McGrail MR, Keene LJ, Rambaldo S, Smith CA, Ray-Barruel G. The relationship between intravenous infusate colonisation and fluid container hang time. J Clin Nurs. 2009 Nov;18(21):3022-8.

- The link between bloodstream infections & extended IV hang time. Physician’s Weekly. Nov 26, 2021. Accessed Oct 10, 2024. Available at: https://www.physiciansweekly.com/the-link-between-bloodstream-infections-extended-iv-hang-time

- Baxter Healthcare Corporation. Lactated Ringer’s Injection, USP, [product information]. Deerfield, IL: Baxter; 2024

- Baxter Healthcare Corporation. Lactated Ringer’s and Dextrose Injection, USP [product information]. Deerfield, IL: Baxter; 2019.

- Baxter Healthcare Corporation. Dextrose and Sodium Chloride Injection, USP [product information]. Deerfield, IL: Baxter; 2019.

- Baxter Healthcare Corporation. Sodium Chloride Injection, USP [product information]. Deerfield, IL: Baxter; 2024

- Baxter Healthcare Corporation. Dextrose Injection, USP [product information]. Deerfield, IL: Baxter; 2020.

- ICU Medical, Inc. Normosol-R pH 7.4 [product information]. Lake Forest, IL: ICU Medical; 2022.

- Intravenous Fluids. In: Morgan GE, Michail MS, Jurray MJ, eds. Clinical Anesthesiology. 4th ed. New York, NY: Lange Medical Books / McGraw-Hill Medical; 2005: 692-696

- Peng ZY, Kellum JA. Perioperative fluids: a clear road ahead? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2013 Aug;19(4):353-8.

- Raghunathan K, Shaw AD, Bagshaw SM. Fluids are drugs: type, dose and toxicity. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2013 Aug;19(4):290-8.